Porter mentioned another measure she and

her husband have taken. Because both work in relatively fragile businesses-

Porter, 42, sells hand-sewn crafts, and Hannon, 48, works for a newspaper- the

couple have prioritized saving for a rainy day. Their emergency account holds

about a year’s worth of living expenses.

Among

our survey respondents only 29 percent had an emergency fund that could cover

three to six months of expenses

But most Americans don’t have even half

that much. Among our survey respondents only 29 percent had an emergency fund

that could cover three to six months of expenses. In a period of prolonged

unemployment, that cushion could be a lifesaver.

Saving a bit at a time- say, $20 a week can

help build your cash buffer. That money should go into an accessible bank or

credit-union savings account.

6. Ignoring your credit report

Consumers can obtain a credit report from

each of the three major credit bureaus – Equifax, Experian, and

Trans-Union-free through the industry’s official website, at

annualcreditreport.com. To most efficiently monitor your credit, we recommend

staggering your report requests to one every four months. But our survey showed

that more than four out of fice people -81 percent- don’t bother checking their

credit reports.

Given that identity theft is the

fastest-growing crime in the country, we think that’s a mistake. Consider what

we heard from a North Carolina doctor who discovered that her office manager

had embezzled at least $500,000 from her practice by using, among other ruses,

credit cards taken out in the practice’s name. The doctored and her husband

later realized that they could have stopped the fraud if only they had checked

their free credit reports. But because they hadn’t needed to borrow in years,

they never bothered.

7. Mismanaging debt.

Credit cards generate among the most

expensive type of consumer debt; the average interest rate is about 14:3

percent, according to LowCards.com, a credit-card comparison website. In spite

of those lofty costs, almost half of our survey respondents with credit cards

said they carry a balance on their cards. Eight percent reported at least one

late payment in the past 12 months. Almost one fifth- 18 percent – said they’d

accrued a balance of $10,000 or more.

Focus

on retiring your debt by paying more than the minimum due each month

To begin to free yourself from that

balance, consider consolidating your debt with a home-equity line of credit;

rates on HELOCs average between 4 and 5 percent, according to Bankrate.com. if

you don’t own a home or lack sufficient equity or income to qualify for a

HELOC, consider transferring your balance to a lower-cost card. Many cards

offer 0 percent financing on balance transfers for 12 to 18 months, after which

the rate will jump to between 12 and 22 percent. You also might have to pay a

fee of 3 or 4 percent of the balance up front.

Focus on retiring your debt by paying more

than the minimum due each month. To that end, put the entire amount you’ll need

each month to pay down your credit cards into a separate bank account so that

you’re not tempted to use it for something else. You can even arrange for the

sum to be direct-deposited from your paycheck.

J. Henry, 80, a retired health-care

executive from Jacksonville, Fla., says he began employing his form of debt

management 23 years ago. Burned by a bad business deal and sitting on $50,000

in credit-card debt, Henry began tracking his family’s spending to bring their

finances back from the brink. Within about four years he had eliminated the

cred his net worth to be credit-card debt- and he hasn’t kept a balance since.

Today, he estimates his net worth to be “north of $1 million.”

Just 35 percent of our survey respondents

say they have a budget, but maybe more ought to. “When I look back, it helped

me keep an eye on where I was financially,” Henry says. “If you just stick to

basics and common sense, you can be OK.”

Even personal-finance gurus make mistakes

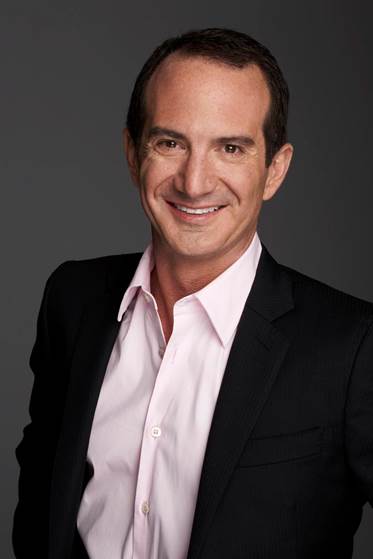

David

Bach

Author of “Debt Free for Life” and founder

of FinishRich Media

I picked up three credit cards and a charge

card for a stereo store while in college. I used them foolishly for things I

wanted but didn’t really need, figuring I could make the minimum payments. By

the time I graduated in 1990, I owed over $12,000. I remember still the

head-spinning feeling of opening those bills. It took me two years to pay it

all off, and I’ve never carried credit-card debt since.

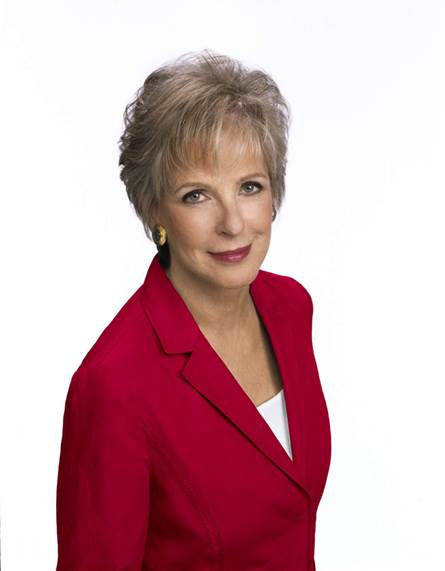

Jane

Bryant Quinn

Personal-finance columnist and author

In the 1980s, a neighbor told my husband

and me that he was investing in a new jeans company. I loved the jeans. We

talked with his partner, looked at his business plan, and invested $25,000.

Well, the partner had misrepresented himself, and our neighbor didn’t share

some key information. The investors lost everything. We didn’t do our due

diligence; we just trusted what we were told.

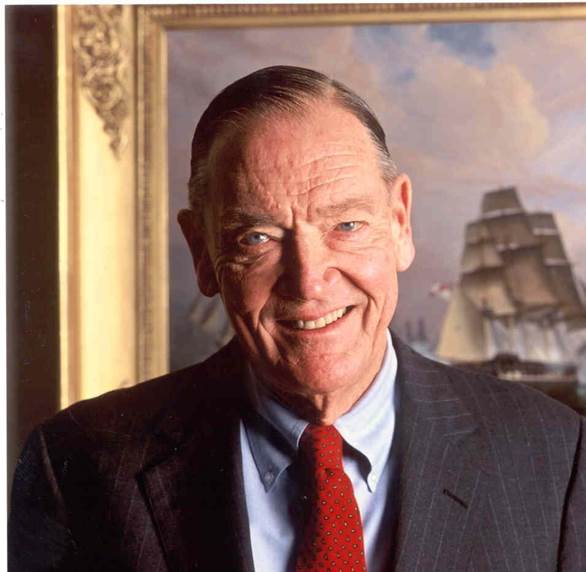

John

Bogle

Founder and former CEO of the Vanguard Group

When I started working I did what everybody

else did backing the 1950: I got a broker. That was biggest mistake I ever

made. I got nowhere. The broker would say, buy this and sell that. Most of the

returns were indifferent. It was complicated to report on my tax returns. More

than half the time when he told me to sell, I should have bought. I haven’t

invested in individual stocks since the 1950s.

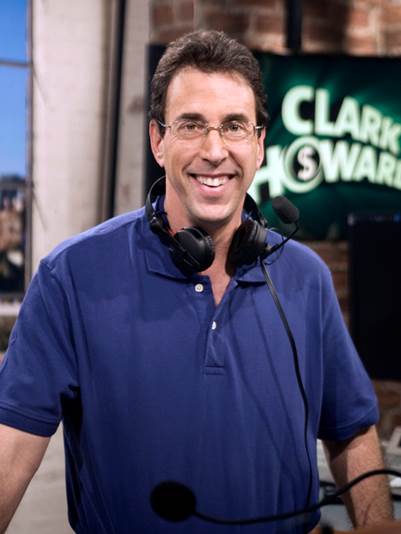

Clark

Howard

TV and radio consumer finance expert.

In 1985 I went into a partnership that

bought into an apartment complex in Miami. Under the tax laws then, you went

into such deals assuming that you’d lose money. You got roughly $2 in tax

benefit for every $1 you lost. In 1986 the tax laws changed. The deal went bust

and I got hit with massive tax bill known as recapture. I learned not to make

investments just for tax reasons.