Right now (Con’t)

Enlist

food favorites.

After dosing rapid-acting insulin, it’s

important to eat some food containing carbohydrate, but fussy eaters may

refuse. Rose’s solution: Find a food item with the number of carbs your child

is supposed to eat per meal, and make sure you have it at the ready. When her

daughter Adalyne turned her nose yp at lunch or dinner, Rose would whip up a

serving of oatmeal with about 30 grams of crabs.

Enlist

food favorites

Set your

alarm.

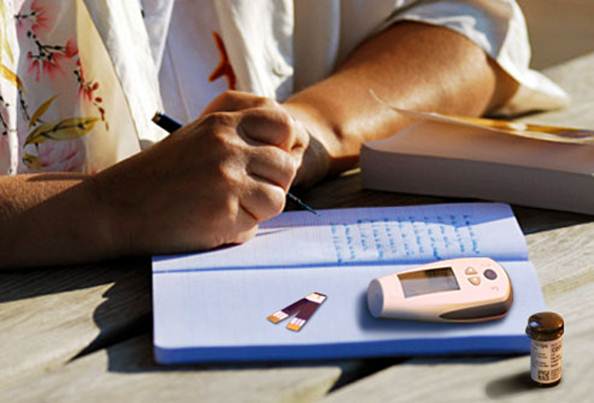

Prepare to check yout child’s blood glucose

during the middle of the night (2 to 3 a.m.) as you adjust overnight insulin,

to catch or prevent any hypoglycemic episodes and to log patterns. Overnight

checks are also important if your child is ill ot physically active in the

afternoon or evening. While there’s nothing you can do to prevent exhaustion

from those interrupted nights, there are steps you can take to make the process

easier. For starters,buy a headlamp, says Rose. It left her hands free for

testing her daughter’s blood glucose in the dark.

Prepare

to check yout child’s blood glucose during the middle of the night (2 to 3

a.m.)

Many children, including those of the parents

interviewed for this article, sleep right through nighttime checks. You will

have to wake them, however, if their blood glucose dips too low. In that case,

it helps to have a quickly digested source of glucose, such as glucose gel or

juice, nearby.

Check blood ketones. On sick days (even with

normal or only slightly elevated glucose levels) or when blood glucose gets too

high – usually over 250 mg/dl – you’ll need to check your child for ketones.

They are waste products that build up when there’s not enough insulin available

in the body. Left unchecked, high levels of ketones can lead to diabetes

ketoacidosis and even death. Most people with type 1 diabetes check ketones

using a simple urine test, but the process is a bit more difficult for babies

and toddlers who haven’t been potty trained. Talk with your provider about

blood ketone tests that work similarly to blood glucose meters. But keep in

mind, they’re less commonly prescribed than urine ketone test kits and may not

be covered under your insurance.

Very

soon

Inject with less pain. Most diabetes experts

will tell you that needles today are tiny, and that’s true – they’re shrunk

considerably since the advent of insulin. But that

doesn’t mean shots are always painless. That said, there are steps you can take

to make an insulin injection inflict as little pain as possible. Many parents

rely on ice for injections. Numbing gel (available over the counter or by

prescription) is a good option for insulin pump infusion set insertions, but it

can take up to an hour to work.

Are

you using room-temperature insulin?

If your child is complaining about the pain

of an injection, first consider your technique. Are you using room-temperature

insulin? Injections hurt more when insulin is cold. Open vials or pens at room

temperature can be used for 30 days. Cold insulin will also result in more air

bubbles, increasing pain. (And you lose insulin to the air bubbles, a

significant amount when it comes to child-sized doses.) Are you quickly poking

the needle through the skin and keeping the barrel steady? When the tip of the

needle rests on top of the skin, the nerves become irritated and pain is

magnified.

The type of insulins you use may matter,

too. Insulin glargine (Lantus) has a tendency to sting because of the

preservatives in it. If it’s causing your child enough of a problem, talk with

your endocrinologist, says Maahs, because he or she may prescribe insulin

detemir (Levemir) instead.

Let

‘em play.

Gee encourages the kids she works with to

participate in what she calls medical play. If your hospital doesn’t offer the

activity, guide your kids through it at home by teaching them to give mock

blood glucose tests and insulin injections (just make sure the syringe is empty

and the needle is removed) to their stuffed animals. Even using a lancing

device on a doll or toy can help kids see there’s nothing to fear.

Get

rid of the guilt.

True, a diabetes diagnosis requires you

cram a semester’s worth of knowledge into just a few days, but for most

parents, studying up on the how-tos of diabetes management isn’t the biggest

source of stress. That’s reserved for feeling guilty about testing their little

one’s blood glucose and giving insulin injections. “When you’re pricking her

finger, she just doesn’t understand,” says Red Maxwell, whose daughter Cassie,

now 16, was diagnosed with type1 diabetes at 18 months old. “That can be really

traumatizing for a parent because you’re hurting your child – the opposite of

your instincts.”

Get

rid of the guilt

The key to shaking off the guilt, says Gee,

is to change the way you view testing and injections. “In the first two weeks,”

says Rose, “[my daughter] was very resistant to it, and it often took two of us

to check her blood sugar, one of us to restrain her and one of us to test her.

I had to separate it in my mind that every shot I was giving her was prolonging

her life.”