Diet and exercise can help

A GDM diagnosis can serve as an early warning,

motivating at-risk women to make permanent lifestyle changes. “Even if

treatment only delays diabetes by 10 or 15 years, that’s huge,” Metzger says.

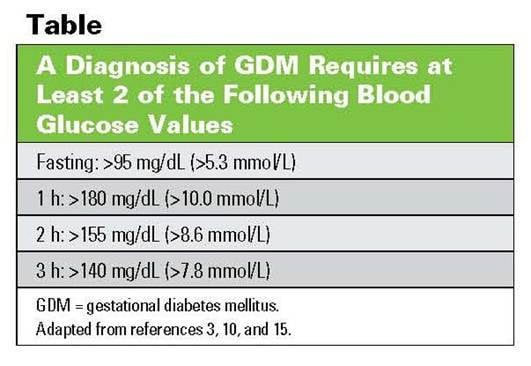

GDM

diagnosis

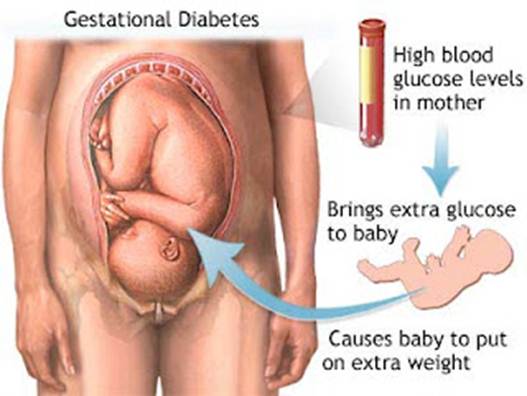

Hillier found the risks to children were

reduced when women with GDM were treated with diet changes, such as eating

fewer sweets and starchy foods, smaller, more frequent meals and more fruits

and vegetables; increased exercise; and, if that was insufficient, by adding

medication, typically insulin. When women remained untreated, their baby’s

risk of being overweight or obese at ages 5 to 7 was nearly twice as high. “But

the children of women who were treated for GDM had no greater risk of obesity

or being overweight compared with children of mothers who had normal blood

sugar during pregnancy,” Hillier says. “This suggests that treating moms during

pregnancy gives their babies a fighting chance for a normal metabolism.”

Like Paetsch, Jennie Wolter, 32, was

shocked by a GDM diagnosis because she, too, had no obvious risk factors. “But

I came to terms with it when I was assured by my health care providers that I

could manage the risks and have a healthy baby,” says Wolter, the community

relations manager for a nonprofit organization in Sacramento, Calif. In

addition to changing her diet with the help of her midwife, a nutritionist, a

nurse and a supervising OB, Wolter also credits exercise with helping her

avoid having to take insulin. “My team told me that blood sugar could be well

controlled by getting some exercise after each meal,” she says. When Wolter

delivered her 8-pound, 6-ounce baby vaginally, she was only 15 pounds over her

pre-pregnancy weight—with her caregivers’ blessing.

Diagnosis

of diabetes during pregnancy

Paetsch did need to take insulin during her

pregnancy, and she credits her diet and exercise changes for feeling better

physically at that point than she had in a long time, for weighing about 10 to

12 pounds less today than when she became pregnant and for teaching her a

healthier way to live, long-term. “Monitoring my diet was a huge pain at the

time, but I learned a lot about how much self-restraint I could actually have,”

she says. She also learned she could fit in small amounts of exercise

throughout the day and have it count, the way experts say it will. “GDM felt

like such a devastating diagnosis at the time,” Paetsch says, “but it was

actually a bit of a blessing in disguise.”

Life after gestational diabetes

“To date, no intervention has been proven

to prevent gestational diabetes [GDM],” says Mark Landon, M.D., chairman of the

department of obstetrics and gynecology at The Ohio State University College

of Medicine. “However, there is evidence that diet, exercise and medication

can help women with a history of gestational diabetes avoid developing

diabetes postpartum.”

Pregnant woman in kitchen eating a salad

Breastfeeding may help as well. A 2012

study published in Diabetes Care found that women who’d had GDM and were

exclusively or mostly breastfeeding at six to nine weeks postpartum had

improved fasting blood glucose levels compared with women who were mostly or

exclusively formula- feeding their babies. More research is needed to determine

if the benefits are long-lasting, Landon says.

Nursing may also help their children.

Researchers reporting this year in the International Journal Of Obesity

studied children from birth to age whose mothers had any type of diabetes and

found that those who’d gotten at least six months of mother’s milk had

significantly lower BMIs, smaller waists and less body fat than the offspring

of diabetic mothers who breastfed less.