3. If my cholesterol levels are good, it’s safe to eat lots of red meat

Prepared properly, in modest amounts, red

meat can be a part of a healthy diet; among other things, it's rich in readily

absorbed iron. However, there's good evidence that eating more than 500 grams

(roughly a pound) per week is associated with an increased risk for colon

cancer, a risk level that appears to continue climbing in tandem with the level

of consumption.

If

my cholesterol levels are good, it’s safe to eat lots of red meat

"Red meat by itself puts more iron and

saturated fat into the digestive system, and a lot of the iron goes undigested

and ends up in the colon," explains James Kirkland, an associate professor

of human health and nutritional sciences at the University of Guelph. Iron is a

pro-oxidant, meaning it produces by-products that can damage cells, which, over

time, could trigger tumour formation.

Kirkland adds that the relationship between

colon cancer and red meat consumption increases with cooking time and

temperature: the more well done the meat, and the hotter the stove or grill,

the greater the risk. "The chemistry behind that is very well

recognized," he says. "When you start cooking the meat more

extensively, carcinogens form."

4. All types of peanut butter reduce diabetes risk.

There's good research linking peanut and

peanut-butter consumption with a variety of health benefits, including a

decrease in Type 2 diabetes risk, but you may be missing out, depending on the

brand you buy.

All

types of peanut butter reduce diabetes risk.

"In the United States, if a product

contains less than 90 percent peanuts, it must be called a peanut-butter

spread, but Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency do not have

any such regulation, "Schwartz explains. Consequently, the contents of the

jar in your cupboard could be something more akin to peanut-flavoured icing,

since some brands contain ingredients such as icing sugar, unhealthy fats, and

corn-syrup solids. (Incidentally, since peanuts contain healthy fats,

reduced-or low-fat versions aren't desirable: the fat content is cut by

substituting non-nutritious fillers.) "You're not going to get the same

health benefits if the product contains 75 per cent peanuts as you would if

it's 95 per cent or 100 per cent peanuts," Schwartz stresses.

So how can you choose a peanut-butter brand

that's most likely to deliver on the health promises held out by research?

Check the list of ingredients on the label: the best options will contain only

peanuts. Another tip: "Look at the amount of protein listed on the

label," suggests Massimo Marcone, an associate professor in the Department

of Food Science at the University of Guelph. "The higher the level of

protein, the more peanuts the product contains, and the less carbohydrate and

other fillers."

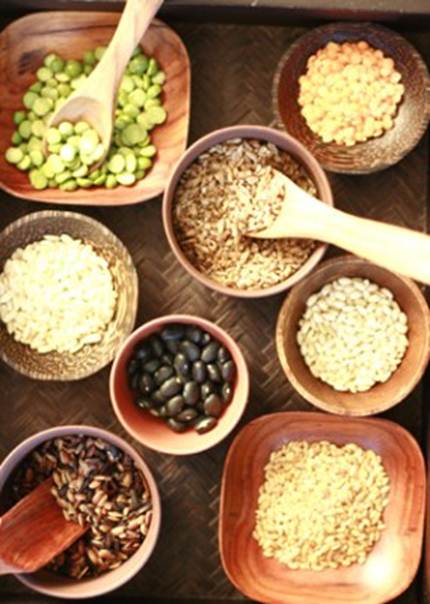

5. "Whole wheat" equals "whole grain."

"When you see 'whole wheat' or '100%

whole wheat' on the label, you assume you're getting a whole grain,"

Schwartz says, "but maybe not."

whole

grains equal

While writing a column for the National

Post, Schwartz discovered that, according to Canadian regulations, flour

can have much of the germ (the most nutritious part of the grain) removed and

still be labeled "whole wheat." (In fact, the product that prompted

Schwartz to probe the rules around flour labeling was a brand of white flour

with added bran that carried the claim "contains the goodness of whole

wheat.") What's more, even many nutrition professionals were un aware of

the loophole. "I contacted people at Ryerson who teach nutrition—they

didn't know," Schwartz says. "I did a survey of dietitians across the

country—and they didn't know."

So how can you tell if your so-called whole

wheat flour hasn't had most of the germ stripped away? "You have to look

for the words' whole grain whole wheat'" on the ingredients list, Schwartz

says.

|

Another Diet Myth Debunked

"Another huge myth is that weight

management is equally about exercise and food—and it's just not," says

Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, an obesity expert and the medical director of the

Bariatric Medical Institute in Ottawa. "Even people who believe exercise

to be a tremendous benefit calorically to weight loss will tell you it's

primarily food, with perhaps 80 per cent of a person's weight relatable to

his or her dietary choices, and 20 per cent to fitness." (Of course,

that's to say nothing of the many other benefits of exercise, such as the

ability to help improve your blood fat profile and blood pressure and to

boost the body's sensitivity to insulin.) True, in theory it doesn't matter

whether you cut calories from your diet or use them up by exercising, but the

latter is much more difficult than people realize.

"One of the struggles people have is

they feel exercise earns them the right to indulge a bit more,"

Freedhoff observes, "and the moment that occurs, you can pretty much

kiss any caloric benefits of exercise goodbye. I can eat a chocolate bar or

drink an energy drink in about a minute, but it's going to take me 40 minutes

of exercise to get rid of those calories. To lose a pound through exercise

requires a marathon of effort. You just can't out-train a bad diet."

|