Getting patients and doctors to change

their approach to cancer screening is hard. But a number of organizations are

working on the problem

For example, in an initiative called

Choosing Wisely, we are working with more than two dozen medical organizations

to identify overused interventions, including screening tests such as Pap

smears for women younger than 21. Other organizations, such as the Informed

Medical Decisions Foundation, have developed brochures and videos in plain

language to help patients navigate complex medical choices. And the U.S.

Preventive Services Task Force and other groups are working to provide more

nuanced, accurate information on cancer screening tests.

Getting

patients and doctors to change their approach to cancer screening is hard

“Cancer turns out to be a much more

complicated and unpredictable disease than we used to think,” says Virginia

Moyer of the task force. “And the tests we have available to us don’t work as

well as we’d hoped, and can even cause harm.

“Scientific evidence shows that some

cancer-screening tests work, and people should focus on those tests rather than

on screening tests that are only supported by theories and wishful thinking.”

Doctor knows best?

When it comes to cancer screening, most

people do what their doctor recommends. Unfortunately, health care providers

don’t always agree on which tests are necessary. In fact, research suggests

that advice often varies among medical practices.

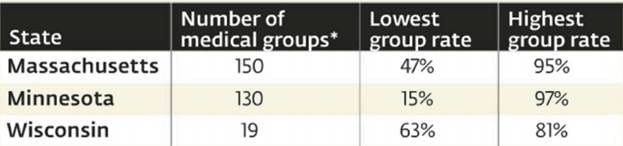

Although health care providers really

publish information on the percentage of their patients who are screened for

specific cancers, we were able to get that information from organizations in

Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Because of differences in the data

collected from each organization, we can’t compare results. But the numbers

illustrate the variation within states, as shown below for colon-cancer

screening.

Percentage

of patients offered colon-cancer screening

(*: A medical group is one or more medical

clinics that operate as a single business.)

Bottom

line.

Don’t assume that your doctor will bring up

cancer screening or follow guidelines. So educate yourself using our Ratings as

a starting point. If you live in one of the states shown below, you can see how

practices compare on the organizations’ websites: for Massachusetts, mhqp.org;

Minnesota, mnhealthscores.org; Wisconsin, wchq.org.

Three tests to get – and eight to avoid

Screening tests for cervical, colon, and

breast cancers are the most effective tests available, according to our first

Ratings of cancer screening tests. But most people shouldn’t waste their time

on screenings for bladder, lung, oral, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, skin, and

testicular cancers.

Notes that our recommendations often differ

with age. For example, colon-cancer screening gets our highest Rating for

people age 50 to 75 but our lowest Rating for those 49 and younger, because the

cancer is uncommon among younger people.

In addition, the Ratings are for people who

are not at high risk; those who are at increased risk, as well as those who

have signs or symptoms of cancer, may need the test or should be tested sooner

or more often.

Our Ratings are based mainly on reviews

from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and independent group supported

by the Department of Health and Human Services. We also considered other

factors: evidence that emerged after the task force’s report; the number of

people affected by the cancer; the cost of testing and treatment; and the

benefits of a test beyond its ability to detect cancer.

Do the benefits of the test outweigh the harms?

|

Very likely

|

5/5

|

|

Likely

|

4/5

|

|

Normal

|

3/5

|

|

Unlikely

|

2/5

|

|

Very Unlikely

|

1/5

|

Get these screenings

Cervical

cancer

Women

age 21 to 30 should have a Pap smear every three years. Those 30 to 65 can go

fice years between Pap smears if they have had HPV testing.

5/5 for women age 21 to 65

1/5 for women of all other ages

A pap smear (a

microscopic analysis of cervical tissue samples) and a human papillomavirus

(HPV) test, which looks for the virus that can cause the cancer

Women age 21 to 30 should have a Pap smear

every three years. Those 30 to 65 can go fice years between Pap smears if they

have had HPV testing. High-risk women may need to be screened more often women

65 and older don’t need to be tested as long as they’ve had regular screenings

when they were younger. Women under 21 don’t need to be screened because the

cancer is uncommon before then and the tests are not accurate for them.

A family history of the disease, a history

of HPV infection, using birth-control pills for five or more years, having

three or more children, and having weakened immunity because of HIV infection

or other causes.

Colon cancer

People

age 50 to 75 should be regularly screened.

5/5 for people age 50 to 75

3/5 for people 76 to 85

2/5 for people 86 and older

1/5 for people 49 and younger

Colonoscopy (exam of the entire colon with

a flexible scope) every 10 years, sigmoidoscopy (exam of the lower third of the

colon) every five years plus a stool test every three years, or a stool test

every year.

People age 50 to 75 should be regularly

screened. Older people should talk with their doctor about the benefits and

harms of the test based on their health and risk factors. Younger people should

consider testing only if they are at high risk, because the cancer is uncommon

before age 50.

A family history of the disease or a

personal history of precancerous polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, obesity,

smoking, type 2 diabetes, excessive alcohol consumption, and a diet high in red

or processed meats.

Breast cancer

Women

age 50 to 75 should have mammograms every two years

4/5 for women age 50 to 74

3/5 for women 40 to 49

2/5 for women 75 and older

1/5 for women 39 and younger

Mammogram (an X-ray of the breast)

Women age 50 to 75 should have mammograms

every two years. Women in their 40s or those 75 and older should talk with

their doctor to see whether the benefits outweigh the harm based on their risk

factors women younger than 40 should consider testing only if they are at high

risk, because the cancer is uncommon at that age

A personal or family history of the cancer,

a personal history of benign breast conditions such as atypical hyperplasia,

dense breasts, menstrual periods before age 12 or after age 55, not having a child

before age 30, postmenopausal hormone-replacement therapy, obesity, excessive

alcohol consumption, smoking, or genetic susceptibility.